A work of art can offend for one reason or another, but is

there ever a good reason for destroying one? The following example is a case in

point.

Destroying works of art

There have been many cases down the centuries of works of

art being deliberately destroyed for one reason or another. Sometimes it is for

ideological reasons, such as when the Taliban in Afghanistan reduced the 6th

century Buddhas of Bamiyan to rubble in 2001; or it can be because someone

simply abhors the work itself, an example being the burning of Graham

Sutherland’s portrait of Sir Winston Churchill by Lady Churchill soon after its

completion in 1954.

A more recent example of a desire to destroy a painting

because of what it portrays, rather than its artistic merit, arose in Russia in

2013. Vasily Boiko-Veliky is a wealthy businessman who has the ear of senior

members of the Russian Government. He is therefore the sort of man whose views

tend to get taken seriously.

Ilya Repin’s portrayal of Ivan the Terrible

Vasily Boiko-Veliky has taken exception to a painting by

Ilya Repin that dates from 1885. It depicts Tsar Ivan IV (“Ivan the Terrible”)

in despair as he holds his dying son and heir, also called Ivan, after the

older Ivan had attacked the younger in a rage and hit him on the head with a

sceptre. The full title of the painting is: “Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan

on November 16, 1581”.

Boiko-Veliky’s objection to the painting was that it cast a

negative light on one of Russia’s greatest historical figures. He is quoted as

saying that the painting “offends the patriotic feelings of Russian people who

love and value their ancestors”. He wanted the painting either to be destroyed

or, at the very least, removed from public display in Moscow’s Tretyakov

Gallery.

He claimed that the murder of one Ivan by the other is a

myth that was invented by foreigners. However, the fact remains that Ivan

Junior did pre-decease his father, which meant that the next tsar was Ivan the

Terrible’s youngest son (the eldest had died in infancy), Fyodor, who was

mentally unstable and unsuited to the role.

An interesting feature of attempts to deny that Ivan the

Terrible killed his son is the fact that the event was apparently witnessed by

Ivan’s chief minister Boris Godunov, who received blows from the sceptre when

he tried to intervene. If the facts were incorrect, could it be that Godunov

was part of a plot to hide the truth? Godunov acted as regent to Fyodor when he

became tsar, and took the throne himself when Fyodor died in 1598.

Not the first time

Strange to tell, Vasily Boiko-Veliky is not the first person

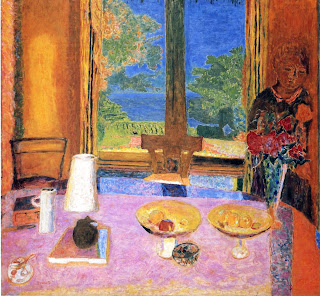

who has taken a profound dislike to the painting in question. The illustration

here is of part of the painting after it was attacked by a vandal in 1913. A

number of knife slashes were made and it took a great deal of careful work to

restore the painting to its previous condition.

Surely there is no good reason to destroy the painting

The point at issue is surely not one of historical accuracy

but the rightness or otherwise of censoring art because it does not convey the

“correct” message. One can admire a work of art from many perspectives, even if

one profoundly disagrees with what it “says”.

This principle applies to all the arts. For example, Vladimir

Nabokov’s “Lolita” is widely recognised as a classic 20th century

novel, despite the detestable nature of its theme. One can appreciate the music

of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss even when one knows just what unpleasant

people they were in terms of their anti-Semitism, which some people claim to

have detected in their music.

When it comes to public art, such as paintings in a gallery,

there is also the question of whether a powerful person has the right to censor

what less powerful people can see. You may not like a painting, for whatever

reason, but nothing can justify your seeking to prevent other people from

making up their own minds.

In the case under discussion, the Russian Minister of

Culture, Vladimir Medinsky, responded by saying that the painting will stay on

display, whatever Vasily Boiko-Veliky says about it. This is particularly

interesting in that Mr Medinsky has actually written a book in which he casts

doubt on the Ivan the Terrible murder story. The two men agree with each other on

the history but take a very different view when it comes to how that history is

presented to people today.

There is also the complication that Ilya Repin is widely

admired in Russia, being held in as much esteem as an artist as Tsar Ivan IV is

as an historical character.

© John Welford