You may well have heard of Barnard’s Star, or possibly even

Plaskett’s Star, but Tabby’s Star? Its less memorable name is KIC 8462852. It

is an F-type main sequence star that is slightly larger and slightly hotter

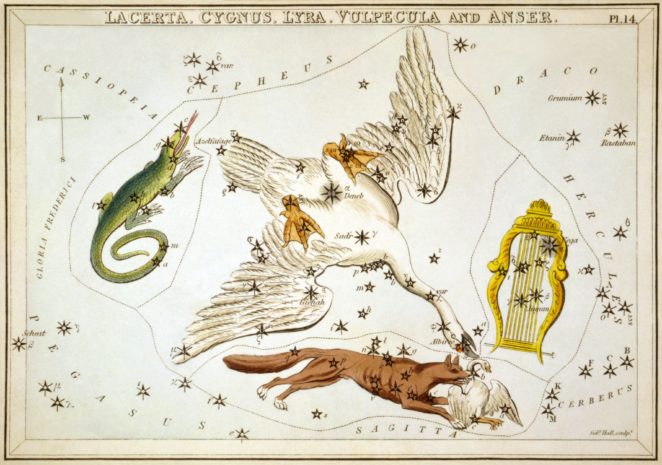

than our G-type Sun. It is about 1,280 light years away from us, in the Cygnus

constellation.

Its name derives from Tabetha Boyajian, an American

astronomer who has been leading a team studying the star as part of a general

search for planets in orbit around distant stars, based on evidence derived

from the Kepler Space Observatory. Tabby’s Star has also been called Boyajian’s

Star, although that does sound a bit less friendly!

The reason why Tabby’s Star has excited interest is that its

“light curve” (an analysis of the light coming from a star over a period of

time) was not what was expected. The search for exoplanets depends on finding

light curves that indicate that a planet is passing in front of its star. The

light will dim for a period of time then return to normal after the planet’s

transit has ceased. This pattern will repeat every time the planet orbits the

star, and consistent data taken over a number of years will enable astronomers

to calculate the planet’s size, mass and distance from its star.

However, the data from Tabby’s star was all wrong. The

dimming that was observed was far from regular and was unpredictable, leading

to all sorts of speculation, including the idea that this was evidence of the

work of an alien civilization on the planet that had built a vast structure to

control the energy being received from its star.

One theory – advanced by a team of astronomers in Colombia –

dispenses with the aliens but proposes an explanation that is just as

intriguing, namely that the planet in question is similar to Saturn in that it

is surrounded by rings.

The theory begins with the notion that a ringed planet, when

transiting its star, would produce different intensities of dimming – less when

only the ring was in transit, more as the full disc of the planet moved across,

and then less again as the “back end” of the ring was all that was obstructing

the star’s light. On each transit the degree of dimming might change if the

angle of the ring was not the same – the planet may well not rotate in the same

plane as its orbit, as we know full well from the behaviour of our own planets.

It would probably take many orbits before a consistent pattern could be

deduced.

The Colombian astronomers modelled this theory based on the

supposed mass of the planet and its closeness to Tabby’s Star, estimated at

about one tenth the distance of Earth to the Sun. They found that the star

would have a gravitational tug on the rings, causing them to wobble and

producing even more irregularity to the light curve.

So the mystery of Tabby’s Star may have been solved. There

is no need to imagine a vast engineering project on the part of an advanced

alien civilization. All that is needed for the observed phenomena – it appears

– is a ringed planet the size of Neptune orbiting close to Tabby’s Star.

However, the jury is still out because this is not the only

theory that has been put forward to explain the mystery of Tabby’s Star.

© John Welford

No comments:

Post a Comment